As Plano and Collin County continue to grow in population and economic activity, municipal elections draw more eyes, more votes, more money and more divisiveness.

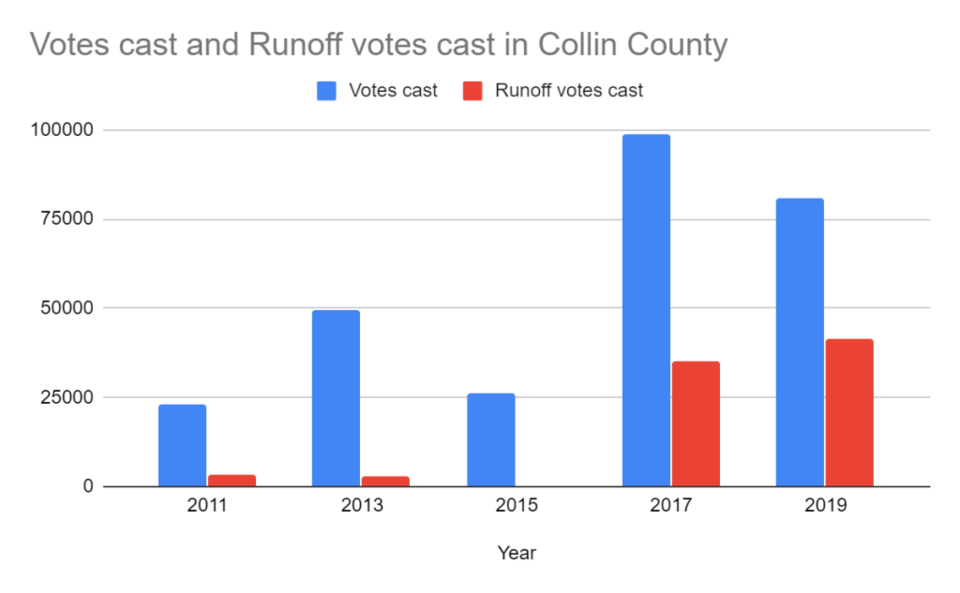

About three times more votes were cast this year than in 2015, the last municipal election that didn’t include a mayoral race.

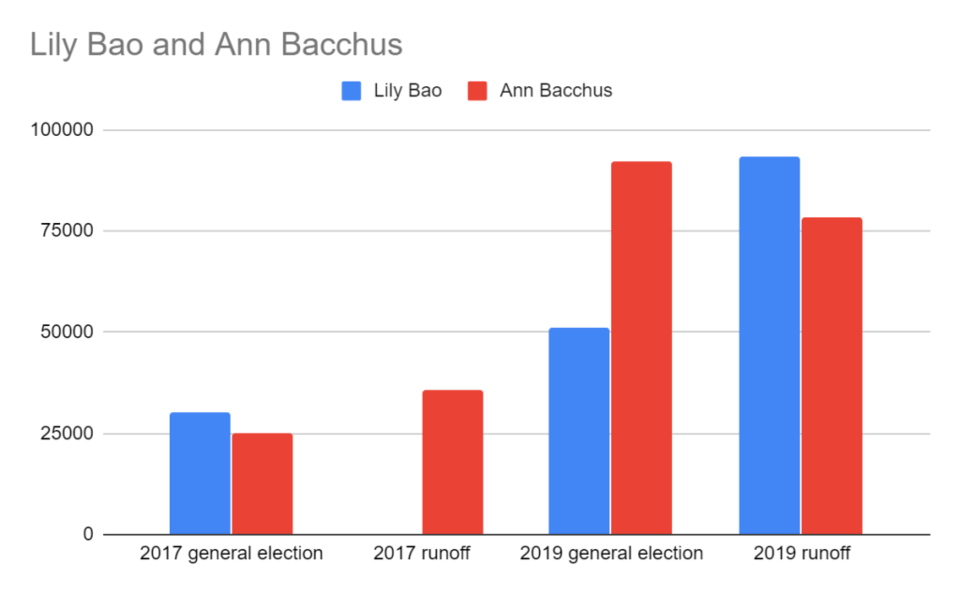

More people voted in the City Council Place Seven runoff election, which pitted Lily Bao against Ann Bacchus for a seat at the table, than in the Place Five runoff election featuring Shelby Williams against incumbent Ron Kelley.

Bao won her race against Bacchus with 56 percent of the vote. Williams won with 53 percent against Kelley.

Both Bacchus and Bao had previously run for council seats in 2017—Bao had challenged incumbent Mayor Harry LaRosiliere for his seat and lost. Her explanation of what went differently this time around is straightforward.

“We won,” she said in an interview a couple of weeks after the runoff.

She added that she had more experience in running from her first time around and that everyone on her campaign worked hard.

“I think our opponent also worked really hard,” Bao said. “They have run a great campaign. We just worked even harder than them.”

But this time around, she also had an endorsement from Gov. Greg Abbott. She also spent more than double what was spent on her 2017 campaign, according to campaign finance reports obtained from the City of Plano website.

And she’s not alone. Both Bao and Bacchus increased their campaign spending by more than two times this year compared to their 2017 campaigns, when combining both general and runoff election expenditures.

The election saw outside donors supporting candidates as well. For example, the We Love Plano PAC, which supported candidates Ron Kelley and Ann Bacchus in their general and runoff elections, saw a $25,000 donations from Aquatech Saltwater Disposal, based in Denton.

“The owners of large housing development companies, road building companies, infrastructure companies in general may well live down in Highland Park, but they do projects all over the metroplex,” said Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Southern Methodist University.

And those developers want to know that elected officials will “take their phone calls,” he added.

But the question of why this election saw more spending and more voting can be accentuated with the observation of another increase: partisanship in a nonpartisan election.

Read: The City of Excellence is in conflict. What is rotten in the state of Plano?

On April 1, Bao announced that Abbott was endorsing her as a candidate, a move unseen before in Plano politics. He also endorsed Shelby Williams that same month.

“Lily Bao will fight for the conservative and free market principles that have made Texas the economic powerhouse it is today,” Abbott said in a statement shared on the endorsement announcement.

Congratulations poured in for both candidates after the announcements. In a social media comment, one resident even thanked Gov. Abbott for “saving Plano."

Jillson said the move has not been seen before in other elections, but partisanship in local elections is not entirely uncommon.

“These are nonpartisan elections,” he said, “but the candidates who run in them have partisan histories. And many people know what those partisan histories are. And the candidates themselves will signal their partisan history if they think it will help.”

Williams said that while knocking on doors to spread the word, almost everybody asked him what party he belonged to.

“There are two ways that could go,” he said. “I could just say, ‘Well, this is a nonpartisan election.’ And it doesn’t answer the question. It hides who I am. Or I could just say, ‘I’m a Republican precinct chair,’ and be honest. If it’s a Republican voter at the door, then they know. If it’s a Democratic voter, they still know. Everybody deserves to know what the people they’re voting for truly stand for.”

Jillson said Republicans tend to share their views with key words like “conservative” or “constitutional conservative” in their platforms while Democrats will keep their affiliations quiet.

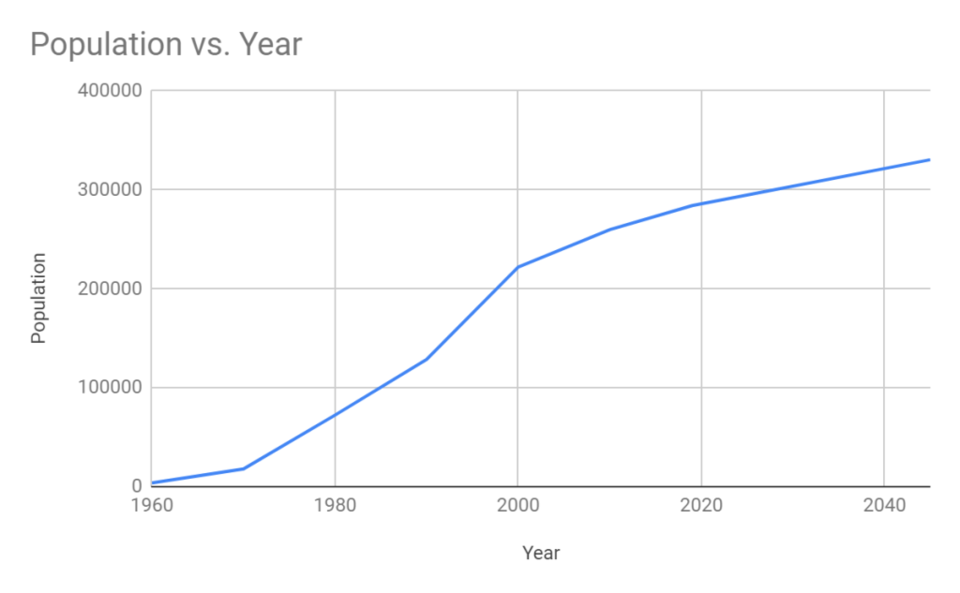

But that could change as Collin County’s demographics continue to morph with two types of population growth, he said.

The first comes from other parts of the United States that are predominantly blue, like California, Illinois and New York. The second features an increase in the number of Asian and Hispanic populations making up the Collin County demographic, Jillson said.

“And both Hispanics and Asians can vote about two to one Democrat,” he said. “Not quite that much in Texas, but in that ballpark. So if you think about migration from other parts of the country and fast-growing Hispanic and Asian populations, that suggests that the deep red character of Collin County is moving toward pink and, at some point, perhaps even toward purple.”

The area won’t see that impact for another 20 years, he said. But the area’s prospective growth still had its weight on the 2019 vote.

According to the city website, Plano’s current population estimate is 284,070, up from 259,857 in the 2010 census. The North Central Texas Council of Governments predicts that by 2045, the population of households in Plano will equal about 330,508. Going by those numbers, Plano's average yearly growth rate will reduce by about 30 percent compared to the growth seen between 2010 and 2019.

Growth is always a major issue in local elections, Jillson said. Candidates will either signal a support of “community development” or “community livability.” In other words, voters have a choice between supporting development as part of population increase or sticking to a caution in growth that protects “neighborhood values and neighborhood livability.”

In 2019, voters across Plano chose livability. They chose a candidate whose advertisements promise to “limit density to keep Plano a thriving suburban community,” as one of Bao’s Facebook banners reads. Voters reacted to growth, largely aiming to establish its margins.

But it’s a growth that seems to be have already begun to slow. Plano is mostly built out, with about five percent of its land left open to development. The vote may be a reaction to the change Plano has seen since numbers shot up starting in the ’70s, but there’s an indication that the growth isn’t as big a force to reckon with as before.

The wave of population growth hit Plano first, but by now, it’s rippled to cities in the county’s outer rim like Frisco. Smaller cities like Anna, Prosper and Celina are watching that wave from a distance and getting ready to surf on that rise.

Plano candidates voted in this year cited traffic as one of the main indicators of a cramped city, but others argue that the traffic is a result of a lack of affordable housing in Plano, which makes the city more of a place to drive through than a place to come back to at the end of the day.

Read: Affordable Housing in Plano is a Million Dollar Question

That may mean a stronger push in the council against policies that lean towards development.

Williams said he doesn’t want to be in a hurry when choosing how to use that remaining five percent of land.

“It’s City Council’s job first and foremost to represent the people of Plano, not outside development interests,” he said.

But aside from the development, a big part of why voters chose Bao and Williams came down to property taxes.

This year, the 86th Texas Legislature passed a bill limiting tax increases to 3.5 percent before a city had to run an election for citizens to voice whether or not to increase their property taxes.

The City of Plano has passed property tax increases consistently since the 2011-2012 budget, which approved a 1.66 percent increase in property taxes. Those increases steadily rose until hitting a 7.3 percent increase in the 2015-2016 budget. The city backed off the next year with its increases, had a larger increase the next year and then again lowered this year’s increase to 4.49 percent.

That means the rates adopted by the city from the past five years would all have had to undergo a referendum if adopted under the new Texas law. It also means property tax payments for Plano homeowners has increased by about 40 percent in the past five years.

Both Bao and Williams ran with a platform to combat increasing property taxes. They now join Anthony Riccardelli and Rick Smith who have historically voted against the tax increases at the council table. Bao replaces

Tom Harrison, the other council member who historically fought those increases.

“The voters have spoken. And that's my platform,” Bao said. “I think as a general philosophy or rule, the government should not keep increasing tax burdens on the citizens.”

Williams said that rather than lowering tax rates to offset property value increases, which would keep residents from vastly increasing the amount of taxes they had to spend, municipalities in the area have been “milking” the property value growth.

“The tax rate had been left static for as long as I’ve been in Plano,” Williams said. “I’ve been here sixteen years. It had been left static for a long long time because for much of history, property values kept rough pace with inflation. And it was never a problem.”

But as property values quickly jumped in recent years, those increases in taxes outpaced inflation.

“So people’s taxes were increased a lot more than their income was increased,” Williams said. “And the cost of living was increased. It was just opportunistic. There’s no other way to put it.”

Now that the council has more voters in support of blocking those increases, Williams said that a vote for an effective tax rate in which tax payments don’t increase at all is “almost assured.”

The 3.5 percent cap put in place by the legislature doesn’t take effect until 2020.

“So what you’re going to see across north Texas, and probably across all of Texas, this year is the cities, the counties and everybody getting their last big tax increase in before next year’s dates kick in for property tax reform. But not in Plano,” Williams said. “We’re going to put a stop to it.

In 2015, only one councilman voted against an increase in taxes: Tom Harrison. That increased to three by 2018. In 2019, there are now four candidates who ran on a platform that was against an increase in property taxes.

Jillson said the eventual effects of the new state laws could prove interesting in the future. The money used to build water systems, sewage systems and school systems before the new members of growing population arrived helped keep cities ahead of the game in terms of growth. But the new laws mean a change in the amount of funding available for that kind of preparation.

“So I think the budgets will tighten,” Jillson said. “There's not much question about that. How candidates react to that in future election cycles, we'll see as we go forward.”

This story has been updated with corrected information.

The original version of this article incorrectly spelled Ann Bacchus's name. The chart depicting votes cast in Plano elections originally combined runoff and general election numbers into one column. About three times more votes were cast in 2019 than in 2015. The article incorrectly stated that voter turnout skyrocketed. The 86th Texas Legislature passed one bill limiting property taxes. Property tax payments for Plano homeowners increased by about 40 percent over five years. The chart showing campaign spending by Bacchus and Bao has been updated with corrected numbers and reformatted for clarity. Aquatech Saltwater Disposal is the name of the company that donated to the We Love Plano PAC. Property tax increases steadily rose until hitting a 7.3 percent increase in the 2015-2016 budget. The rates adopted by the city from the past five years would all have had to undergo a referendum if adopted under the new Texas law. The Plano population chart has been updated to include consistent numbers for the 2010 census. Jillson said the second kind of growth featured an increase in the number of Asian and Hispanic populations making up the Collin County demographic. The article incorrectly implied a 50-50 split on key issues like development in Plano and increasing property taxes in the City Council after the 2019 electionthat could spell a stronger pushback in the near future against policy that has historically supported growth and development. It incorrectly said that this year’s budget will probably face intense arguments for each side now that the vote is likely split in half between raising and lowering the property tax rate. We apologize for the errors.

Clarification: Bao and Bacchus spent more than double on their 2019 campaigns than in 2017 if combining runoff and general election campaign spending.

Clarification: After hitting a 7.3 percent increase in the 2015-2016 budget, the city backed off the next year with its increases, had a larger increase the next year and then again lowered this year’s increase to 4.49 percent.