On June 5, 2020, the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor celebrates 100 years of supporting working women through research, policy and standards development, and advocacy. FRASER celebrates the Bureau’s milestone with a look at its origins and its work of the past 100 years.

FRASER holds a unique digital collection documenting the work of the Women’s Bureau, with historical documents on working conditions, wages, home life, workplace regulations, costs of living, health and hygiene, and social issues. The Bulletin of the Women’s Bureau contains the majority of the material and covers a range of topics including industry-specific reports, the legal status of women, and comprehensive handbooks that provide and examine various data points related to women’s employment. The organization’s archival records, digitized in partnership with the National Archives (Records of the Women’s Bureau, Record Group 86), offer a view of the planning, communication, and research behind the Bureau’s mission to serve working women.

FRASER’s history of the Women’s Bureau actually begins before the Bureau’s 1920 founding, with the records of its predecessor, the Woman in Industry Service (WIS). During World War I, the number of women in industry increased, as did the range of occupations available to them. These occupations, while still mostly limited to domestic and clerical services, included factory and industrial work.[1]

In 1917, the Storage Committee of the War Industries Board began to investigate the possibility of employing women to work in Army storage warehouses. At the head of this investigation was pioneering labor researcher Mary Van Kleeck. Through the summer and fall of 1917, Van Kleeck studied labor conditions in warehouses where women were employed, and her final report revealed that not only were women already working in machine shops, armories, and lumberyards in 1917, but their wages, hours, and working conditions were generally poor. To meet the needs of these working women, Van Kleeck recommended the establishment of a women’s work bureau in the War Department, to study and advise on the employment of women in all kinds of work for the military. The WIS was established less than a year later, and President Woodrow Wilson appointed Van Kleeck as its director. For the remainder of the war, the WIS produced field reports documenting working conditions, wage disparities, and instances of discrimination against working women.

After the war, Mary Van Kleeck assisted in writing the legislation to transition the WIS to a new Women’s Bureau in the Department of Labor. The June 1920 act establishing the Bureau enabled it to “formulate policies and standards to promote the welfare of wage-earning women, improve their working conditions, increase their efficiency, and advance their opportunities for profitable employment.” The legislation also stipulated that the organization “shall be in charge of a director, a woman,” and as such, Van Kleeck was appointed as the head of the agency. She resigned after a few weeks (for personal reasons), at which time her colleague Mary Anderson became the first long-term director of the Women’s Bureau, leading it until her retirement in 1944.[2]

Image from “The Outlook for Women as Medical X-Ray Technicians,” Women’s Bureau Bulletin, No. 203-8, 1954.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, as the U.S. enjoyed a time of relative peace but also of economic upheaval, the work of the Women’s Bureau focused on the working conditions of women employed in, for example, the candy, canning, cotton, and clothing (including men’s wear) industries; households; spin rooms; laundries; offices, as bookkeepers and stenographers; and department stores. Early groundbreaking studies focused on African American working women,[3] laws on eight-hour work days, and government positions open to women. Authors of these reports included women research scientists, social activists, and physicians. For example, Alice Hamilton, medical investigator and women’s rights activist, published several reports in the Bulletin on the subject of industrial lead poisoning. She would later become known and respected as the nation’s leading authority on industrial toxicology. During this time, the Bureau also produced its first newsletter (1921-1937), which focused on state legislation affecting working women, the efforts toward a minimum wage, and the advancements of women working in civil service positions.

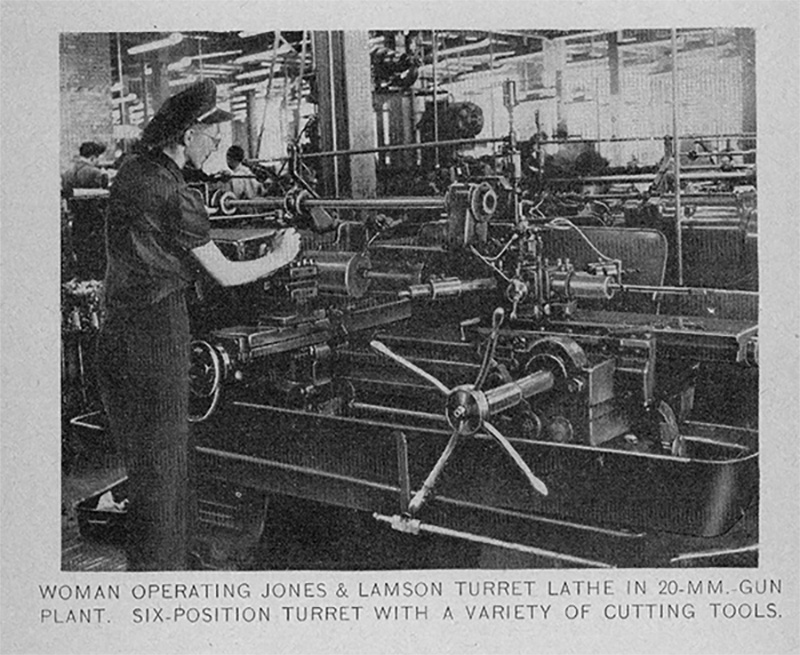

The advent of World War II changed the focus of the nation and expectations for women’s roles in the workforce, giving them opportunities to work in support of war efforts. The Bureau’s second newsletter, The Woman Worker (1938-1942), launched in January 1938. As America’s involvement in the war increased, the newsletter reflected on the lessons learned during World War I and reported on women working in defense industries. Bulletins at the time focused on women employed in the manufacturing of small arms and artillery ammunition, shipyards, aircraft production, and foundries. Other studies from the era addressed the safety of women war workers, the adjustments necessary to ensure appropriate working conditions for them, their wages, and the housing of those who left the home to work.

Image from “Employment of Women in the Manufacture of Cannon and Small Arms in 1942,” Women’s Bureau Bulletin, No. 192-3, 1943.

After World War II, women were expected to transition back to their pre-war lives, giving up their wages in the process. The Women’s Bureau documented the uneasy transition into the postwar period by examining the employment outlook and opportunities for women during this time. Bulletins of the era recommended postwar careers for women in medicine, social services, science, mathematics and statistics, legal work, and radio. In the following decades, the Bureau’s focus turned to women college graduates, encouraging women to consider the education and careers available at the time. During this period, the Bureau produced the newsletter Facts on Women Workers (1946-1961), including national and foreign topics, such as employment figures and projections, wages, and legislation. The Bureau also began publishing pamphlets in mid-1950, providing guidance on job prospects for women, including specific professions and advanced education to pursue.

As the economic landscape of the United States changed through wars, recessions, and other financial crises, the Women’s Bureau researched and documented the changes in women’s occupations (1944, 1954). Uniquely positioned to aid in the development of policies to support working women, the Bureau researched and reported on the evolution of the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938), the Equal Pay Act of 1963, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Through the 1960s and 1970s, the Bureau began to focus on initiatives to support the work-life balance of employed women, publishing several early studies on childcare services and maternity benefits for working women. In 1982, the Bureau announced a major initiative to encourage employer-sponsored childcare, followed by pressure for the passage of the Family Medical Leave Act of 1993.

FRASER currently holds over 700 historical documents created by the Women’s Bureau and is continuously engaged in locating, scanning, and posting available items. Browsing this collection offers a look into the historical importance of the Bureau and the work it has accomplished. For 100 years, the Women’s Bureau has not only helped change the outlook for working women but has also strengthened their role in the American workforce.

[1] Women’s Bureau. History: An Overview 1920-2020.

[2] New York Times. “Mary Anderson, Ex-U.S. Aide, Dies; Directed Women’s Bureau in Labor Department.” New York Times, January 30, 1964.

[3] Researched in conjunction with the short-lived “Division of Negro Economics” within the Department of Labor.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER