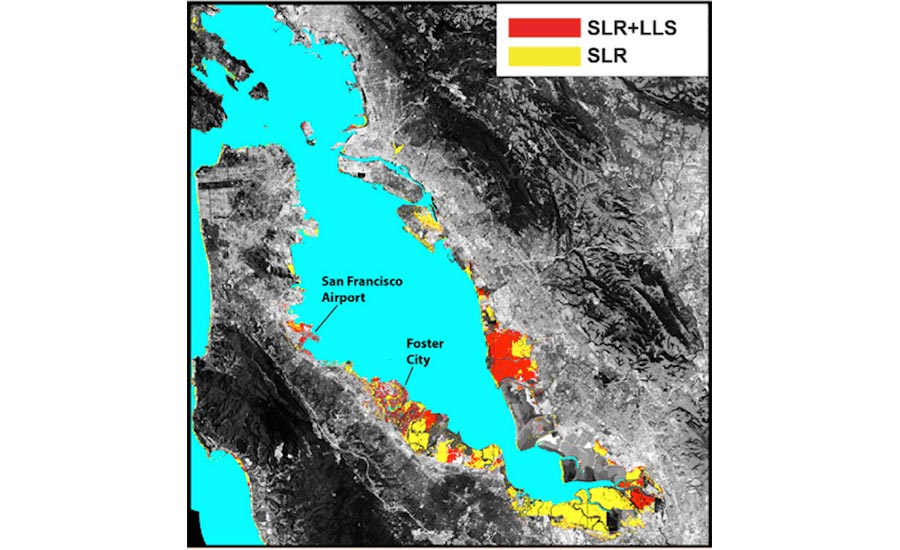

All coastal cities in the U.S. face some potential threat from sea-level rise, but areas around San Francisco Bay may be more vulnerable than previously thought according to a recent study by Arizona State University’s Manoochehr Shirzaei and UC Berkley’s Roland Bürgmann published in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances.

The pair, using a satellite-imaging network that can measure small changes in the earth’s surface, found the problem of rising sea levels is exacerbated in the Bay Area at sites where the soil is sinking at a rate of 10 mm or more per year. The subsidence problem is in addition to sea levels rising a mean global average of 3.1 mm per year.

The researchers found previous projections for the Bay Area underestimate the risk of flooding by as much as 90 percent because they don’t take into account the rate of soil subsidence.

“The FEMA maps of the Bay Area need to be updated with the measurements of land subsidence and projection of sea level rise,” says Shirzaei. “By revising the maps, local authorities can make better flood resilience plans.”

Of particular concern are parts of the city built on landfill materials or ancient mud deposits. Subsidence is occurring at San Francisco International Airport (SFO), Foster City and Union City five times the rate of areas built on more solid ground. The problem is most acute on Treasure Island, the site of a $1.5 billion redevelopment project, which is seeing subsidence rates of up 19 mm per year, according to Shirzaei.

“We are already noticing the effects, in particular at SFO where runways are continually cracking and are sometimes flooded,” Shirzaei says.

Doug Yakel, Public Information Officer for San Francisco International Airport, says the cracking and flooding are not necessarily evidence of subsidence.

“While part of SFO is built on landfill, most pavement failures here happen in areas where the largest amount of aircraft movement occurs,” he explains. “Water on runways and taxiways is typically the result of drainage issues following periods of rainfall.” However, the airport is addressing sea-level rise and over the past 30 years has installed earth berms, sheet-pile walls and concrete walls, installed along the airport’s eight miles of shoreline.

The answer to subsidence and sea level rise in learning to build differently for the coming era, says Kristina Hill, an associate professor of environmental planning at UC Berkley.

“There’s no way we can afford to build levees and walls to prevent future saltwater flooding,” Hill explains. “So we’re looking at things like dredging channels along the shore and using the soil to build up the land for taller buildings, or creating artificial ponds and putting prefabricated three to four-story structures onto shared floating decking.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment